International Studies Director Dr. Andrea Duffy was recently featured in The Conversation. Read her story on Ottoman History and climate change below, or visit theconversation.com.

What the Ottoman Empire can teach us about the consequences of climate change – and how drought can uproot peoples and fuel warfare

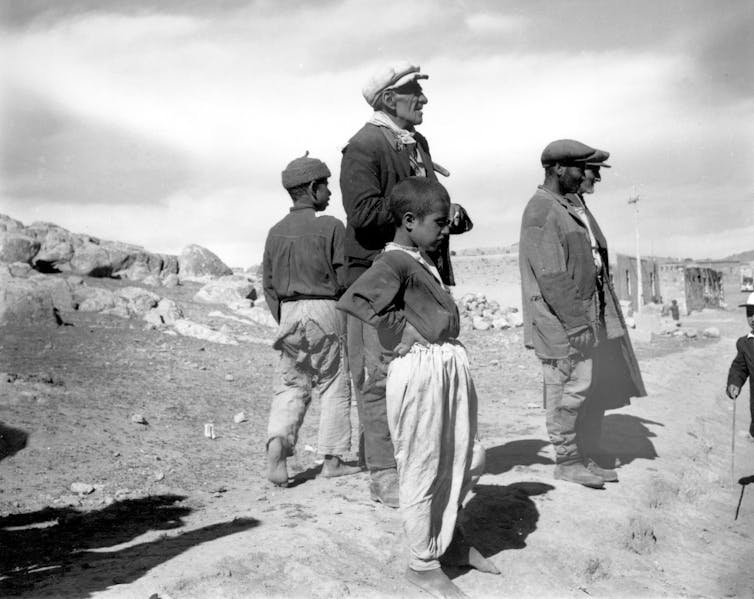

Drought’s effects on the population slowed the Ottoman Empire’s expansion in the 16th century. Lessing Archives

Andrea Duffy, Colorado State University

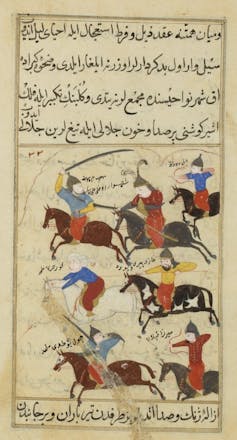

In the late 16th century, hundreds of bandits on horseback stormed through the countryside of Ottoman Anatolia raiding villages, inciting violence and destabilizing the sultan’s grip on power

Four hundred years later and a few hundred miles away in the former Ottoman territory of Syria, widespread protests escalated into a bloody civil war in 2011 that persists to this day.

These dark episodes in Mediterranean history share key features that offer a warning for the future: Both forced waves of people from their homes. Both were rooted in politics and had dramatic political consequences. And both were fueled by extreme weather associated with climate change.

As an environmental historian, I have researched and written extensively about conflict and environmental pressures in the Eastern Mediterranean region. While severe droughts, hurricanes, rising oceans and climate migration can seem new and unique to our time, past crises like these and others carry important lessons about how changing climates can destabilize human societies. Let’s take a closer look.

Drought in the heartland of an empire

We live in an era of global warming largely due to unsustainable human practices. Generally known as the Anthropocene, this era is widely considered to have emerged in the 19th century on the heels of another period of major global climate change called the Little Ice Age.

The Little Ice Age brought cooler-than-average temperatures and extreme weather to many parts of the globe. Unlike current anthropogenic warming, it likely was triggered by natural factors such as volcanic activity, and it affected different regions at different times, to different degrees and in vastly different ways.

Its onset in the late 16th century was particularly noticeable in Anatolia, a largely rural region that once formed the heartland of the Ottoman Empire and is roughly coterminous with modern-day Turkey. Much of the land traditionally was used for cultivating grain or herding sheep and goats. It provided a critical food source for the rural population as well as residents of the bustling Ottoman capital, Istanbul (Constantinople).

The two decades surrounding 1600 were especially tough. Anatolia experienced some of its coldest and driest years in history, tree rings and other paleoclimatological data suggest. This period also had frequent droughts, frosts and floods. At the same time, the region’s inhabitants reeled under an animal plague and oppressive state policies, including the requisitioning of grain and meat for a costly war in Hungary.

Prolonged poor harvests, war and hardship exposed major shortcomings in the Ottoman provisioning system. While inclement weather stalled state efforts to distribute limited food supplies, famine spread across the countryside to Istanbul, accompanied by a deadly epidemic.

By 1596, a series of uprisings collectively known as the Celali Rebellion had erupted, becoming the longest-lasting internal challenge to state power in the Ottoman Empire’s six centuries of existence.

Peasants, semi-nomadic groups and provincial leaders alike contributed to this movement through a rash of violence, banditry and instability that lasted well into the 17th century. As drought, disease and bloodshed persisted, people abandoned farms and villages, fleeing Anatolia in search of more stable areas, while famine killed many who lacked the resources to leave.

Weakening of the Ottoman Empire

Before this point, the Ottoman Empire had been one of the most powerful regimes in the early modern world. It included large swaths of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East and controlled the holiest sites of Islam, Christianity and Judaism. Over the previous century, Ottoman troops had pushed into Central Asia, annexed most of Hungary, and advanced across the Hapsburg Empire to threaten Vienna in 1529.

The Celali Rebellion had major political consequences.

The Ottoman government succeeded in reestablishing relative calm in rural Anatolia by 1611, but at a cost. The sultan’s control over the provinces was irreversibly weakened, and this internal check on Ottoman authority helped curb the trend of Ottoman expansion.

The Celali Rebellion closed the door on the Ottoman “Golden Age,” sending this monumental empire into a spiral of decentralization, military setbacks and administrative weakness that would trouble the Ottoman state for its remaining three centuries of existence.

Climate change as a threat multiplier

Four hundred years later, environmental stress coincided with social unrest to launch Syria into an enduring and devastating civil war.

This conflict emerged in the context of political oppression and the Arab Spring movement, and on the tail end of one of Syria’s worst droughts in modern history.

The magnitude of the environment’s role in the Syrian civil war is difficult to gauge because, as in the Celali Rebellion, its impact was indelibly linked to social and political pressures. But the brutal combination of these forces can’t be ignored. It’s why military experts today talk about climate change as a “threat multiplier.”

Now entering its second decade, the Syrian war has driven over 13 million Syrians from their homes. About half are internally displaced, while the rest have sought refuge in surrounding states, Europe and beyond, greatly intensifying the global refugee crisis.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Lessons for today and the future

The Mediterranean region may be particularly prone to the negative effects of global warming, but these two stories are far from isolated cases.

As Earth’s temperatures rise, the climate will increasingly hamper human affairs, exacerbating conflict and driving migration. In recent years, low-lying countries such as Bangladesh have been devastated by flooding, while drought has upended lives in the Horn of Africa and Central America, sending large numbers of migrants into other countries.

Mediterranean history offers three important lessons for addressing current global environmental issues:

- First, negative effects of climate change fall disproportionately on poor and marginalized individuals, those least able to respond and adapt.

- Second, environmental challenges tend to hit hardest when combined with social forces, and the two are often indistinguishably connected.

- Third, climate change has the potential to prompt migration and resettlement, spur violence, unseat regimes and dramatically transform human societies throughout the world.

Climate change ultimately will affect everyone – in dramatic, distressing and unforeseen ways. As we contemplate this future, there is much we can learn from our past.![]()

Andrea Duffy, Director of International Studies, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.